Iain McGilchrist and the Divided Brain

Iain McGilchrist, a renowned psychiatrist and literary scholar, offers a compelling perspective on human consciousness through his extensive work on the lateralization of brain function, most notably in his seminal book The Master and His Emissary. His exploration of the distinct ways the left and right hemispheres of the brain process information has significant implications for how we understand ourselves, our culture, and the very nature of reality.

At the heart of McGilchrist's work is the understanding that the left and right hemispheres, while interconnected, attend to the world in fundamentally different ways. The left hemisphere tends towards abstraction, categorization, explicit knowledge, and a focus on parts and analysis. It operates with a sense of certainty and control, favoring linear, logical thought. The right hemisphere, in contrast, is characterized by its holistic perception, its grasp of implicit meaning, its appreciation for context and relationship, and its openness to ambiguity and the richness of embodied experience. It understands the whole through pattern recognition and intuition.

McGilchrist contends that Western culture has increasingly privileged the mode of the left hemisphere, leading to a fragmented and overly mechanistic view of reality, often at the expense of the more integrated and nuanced understanding offered by the right hemisphere. This imbalance, he suggests, has far-reaching consequences for our mental health, our social interactions, and our relationship with the natural world.

So, does dual-aspect monism fit into this framework? Dual-aspect monism, as we've discussed, posits a single underlying reality with two fundamental aspects: the mental (subjective experience) and the physical (the objective world). The key is that these are not separate substances but different manifestations of the same underlying unity.

While McGilchrist's focus is primarily on the functional duality within the brain and its impact on our experience of reality, his work hints at a deeper unity that aligns with a dual-aspect perspective. He consistently emphasizes that the brain is a whole, with the hemispheres working in concert, albeit with different roles. The two modes of attention are not entirely independent but are constantly interacting and informing one another. This interconnectedness at the neurological level suggests a fundamental unity underlying the apparent functional division.

The right hemisphere's holistic grasp, its sensitivity to implicit connections, and its appreciation for the embodied and relational nature of existence suggest a reality that is not simply a collection of isolated, quantifiable parts.

One could interpret the distinct modes of attention of the left and right hemispheres as reflecting the two aspects of dual-aspect monism. The left hemisphere's focus on the discrete, the abstract, and the quantifiable could be seen as aligning with our apprehension of the physical world as composed of separate objects and measurable properties. The right hemisphere's holistic, contextual, and embodied understanding could be seen as more closely related to our subjective, conscious experience. Both modes of attention are necessary for a complete understanding of reality, just as both aspects are considered fundamental in dual-aspect monism.

One could argue that the distinct ways our brains attend to the world reflect the inherent duality within a fundamentally unified reality, with the left hemisphere focusing on the explicate order of separate things and the right hemisphere grasping the implicate order of interconnectedness.

So, while Ian McGilchrist's work, grounded in empirical observation and clinical insights, doesn't explicitly advocate for dual-aspect monism, his exploration of the brain's two modes of attention offers a framework that is highly compatible with such a view. ⬚

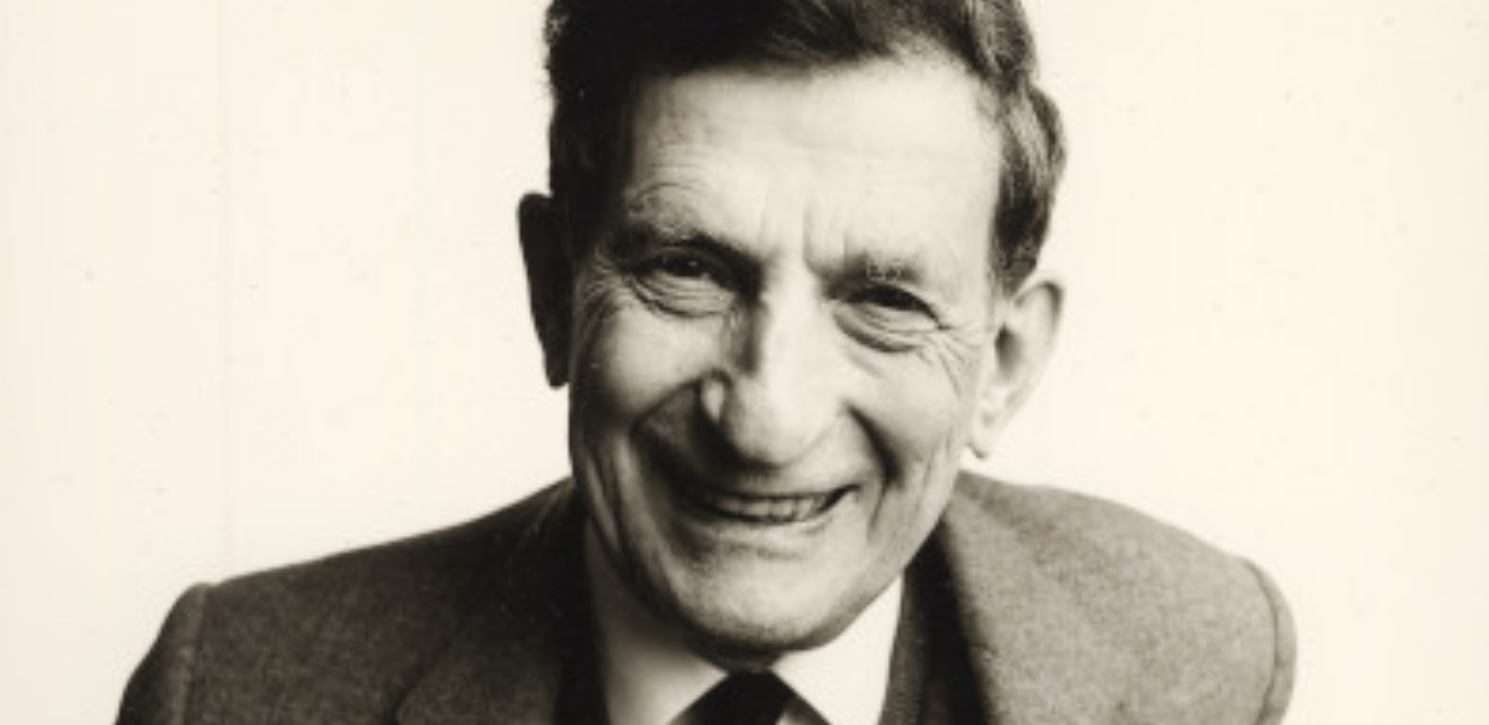

David Chalmers: Beyond the Hard Problem

David Chalmers (b. 1966) is a prominent figure in contemporary philosophy of mind best known for formulating the hard problem of consciousness, the challenge of explaining why and how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experience.

Chalmers initially proposed a naturalistic dualism, arguing that consciousness is a fundamental property of the universe, irreducible to and distinct from physical properties, arising alongside physical properties in the brain. As such, he proposed two distinct fundamentals: the physical and the phenomenal. However, after grappling with the difficulties inherent in any form of dualism, like how distinct properties relate or interact, Chalmers has increasingly explored monistic alternatives that still take consciousness seriously. His recent work has moved towards a position characterized as dual-aspect monism grounded in the concept of information.

Chalmers suggests that information is fundamental to reality. This fundamental information has two inseparable aspects: a physical aspect of structure, processing, and causality, which is objectively describable, and a phenomenal aspect of subjectivity. The underlying reality isn't just physical stuff, nor is it just pure consciousness, but something more fundamental, perhaps proto-conscious properties or information itself, presented in two aspects. When this fundamental information is processed in complex ways, such as in a brain, the conscious aspect manifests as subjective experience while the physical aspect manifests as the observable biological system.

So how does Chalmers’ philosophy square with the nondual understanding?

Points of Agreement:

Rejection of fundamental dualism: The most apparent similarity is the rejection of mind-body dualism as the ultimate nature of reality. Both Chalmers and the nondual understanding assert that the perceived split between inner experience and the outer physical world is not a reflection of two ultimately separate kinds of substance.

Underlying unity: Both frameworks assert a single, underlying reality from which the apparent duality of mental and physical phenomena arises. For Chalmers, this is the fundamental information or proto-psychic substratum, a rudimentary form of consciousness in capacity or potential. As we explore here, it is thought and perception that draws this potential out into manifestation, creating appearances in the world of form.

Consciousness is fundamental: Both agree that consciousness is not a byproduct of the brain or merely an illusion. Chalmers, however, argues that consciousness is a fundamental aspect of reality while the nondual view suggests that consciousness is the fundamental reality.

Aspects/appearances: Both views suggest that the mental and physical are not independent realities but different ways the underlying reality presents itself. Chalmers calls them aspects. For Schopenhauer, its Representation. For Spinoza, its Extension. Here we often say appearances. It’s all the same thing.

Points of Divergence:

The nature of the underlying reality: Chalmers' underlying reality is often described abstractly in terms of information or proto-conscious properties that give rise to both physics and phenomenal experience. While it's the ground, it's not typically identified as pure, aware consciousness itself in the way we identify it here. Nonduality points to the ultimate reality as conscious, self-aware being (the verb), not a potential or structural ground for consciousness to emerge from.

The status of physical reality: In Chalmers' dual-aspect view, the physical aspect is a fundamental way the underlying reality exists, seemingly co-equal with the conscious aspect. Physical reality, as structure and process, is a genuine face of the fundamental. According to the nondual understanding, while the physical world is a real experience or appearance, its reality is considered relative and dependent compared to the ultimate reality of consciousness. The world is the appearance of consciousness, not a fundamental, irreducible aspect in and of itself.

Methodology and goal: Chalmers' approach is primarily analytical and philosophical, seeking to construct a coherent metaphysical theory that accommodates both physical and conscious data. The goal of the theory is to understand the structure of reality. Nonduality emphasizes direct, non-conceptual realization through conscious awareness. The goal here is experiential and simple—to rest consciously as awareness.

From a nondual perspective, Chalmers' philosophy can be seen as a rigorous contemporary Western intellectual framework that arrives at conclusions compatible with nondual ontology. His identification of consciousness as fundamental, his rejection of materialism's reductionism, and his move towards a monistic, dual-aspect view align with the nondual perspective of reality.

However, Chalmers' description of the underlying reality—information, proto-conscious—is still describing the structure of the manifested realm or the bridge to it, rather than the unmanifest absolute ground itself. Or, if it is describing the ground, it is doing so in terms that are still abstract and structural, whereas the nondual realization points to the ineffable, self-aware being that precedes or underlies all structure and information.

David Chalmers' exploration of dual-aspect monism offers a sophisticated way to honor both the physical world and subjective experience within a unified framework. While the precise nature of his proposed underlying reality and his analytical methodology differ from the experiential path, his argument against reductive materialism and his conclusion that reality is fundamentally unified with consciousness is in line with the nondual view. ⬚

David Bohm's Implicate Wholeness

David Bohm, a distinguished theoretical quantum physicist who worked with J. Robert Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein, dedicated much of his later life to exploring the philosophical implications of quantum mechanics. His work led him to propose a view of reality that challenges conventional understanding and aligns closely with dual-aspect monism. While Bohm as a physicist didn’t rigidly apply philosophical labels, his concepts offer a scientific framework for the nondual perspective.

Bohm felt that the Cartesian model of reality—that there are two kinds of substance, the mental and the physical which somehow interact—was too limited. Quantum mechanics, with its nonlocal correlations and the observer effect, suggested a universe far more interconnected than classical physics allowed. To address this, Bohm proposed a new ontology based on the concept of the Implicate Order.

Bohm’s analogy for reality is a hologram. Each part of a holographic plate contains information about the whole image. In the same way, the Implicate Order is the underlying, hidden, undivided reality, a realm of pure potential and dynamic flux. The Explicate Order, then, is the manifest, visible world of objects, space, and time; it is the phenomena that is projected from the Implicate Order.

For Bohm, the universe is in a constant state of becoming, of transformation, which he termed the Holomovement. This undivided wholeness is the source of all forms, both physical and mental. The Implicate and Explicate Orders are aspects or phases of this movement.

Consciousness, intricately linked to the Explicate and Implicate Order, is a dynamic process of unfolding and enfolding, where information from the non-physical reality of the Implicate Order enters into and shapes the physical reality of the Explicate Order. In this view thought and matter are not two different kinds of stuff interacting but fundamentally interwoven processes within the Holomovement.

The central concept of the Holomovement as the ultimate, undivided ground mirrors the nondual assertion that reality is ultimately one. The apparent fragmentation and separation we experience in the Explicate Order is analogous to the nondual concept of maya, the illusion of separateness arising from the one reality.

Bohm’s model provides a framework for understanding how a single reality could consistently present as both subjective experience and objective physicality.

By approaching reality from the rigorous discipline of theoretical physics, Bohm arrived at a metaphysical vision that complements the insights of nondual traditions. His concept of the Holomovement as the undivided ground from which mind and matter unfold provides a scientific argument for a form of dual-aspect monism. This framework offers a modern, physics-informed language to describe a picture of the cosmos that looks remarkably like the undivided reality described by sages and mystics across millennia. ⬚

Jesus' Canonical Teachings of Nondual Reality (Part 1)

While traditionally understood within a framework of a personal God interacting with separate individuals, the canonical texts also contain references to a unified reality.

Clearly, Jesus’ teachings held layers of meaning, and he tailored each to the capacity of his audience. For the larger crowds he spoke in parables, earthly stories with heavenly implications. To his disciples, Jesus was more direct, offering enigmatic insights into the “mysteries of the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 13:11). Even still, his closest followers struggled to understand his meaning. This distinction, then, between public and private instruction as well as the indirect wording, indicates a wisdom that could not be simply stated or intellectually understood. Apprehension required a radical shift in perception.

From a nondual perspective this difficulty in understanding is directly related to the fundamental obstacle that stands in the way of realizing the nature of this unified reality: the belief of being a separate entity in the world. Experience is filtered through the lens of the ego, which constructs a world of “me” and “other,” subject and object. Seeing the world so fundamentally dualistic makes it very difficult to conceive of, let alone embody, a reality of radical unity where such distinctions are ultimately unreal. Jesus' deeper teachings likely point to this unified reality that a mind deeply conditioned by separation cannot readily process.

This awareness of oneness is expressed in the Gospels when Jesus speaks of relationship with one another and to him. In Matthew 25:40, he says, “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.” This is often interpreted as a call to empathy and service. But it can also be seen as a direct expression of the awareness of fundamental oneness. If reality is a seamless, indivisible whole, then an action directed towards any apparent part of that whole is an action directed towards the whole itself. Here, there is ultimately no “other” that is separate from the self, separate from the divine presence embodied as Jesus.

For Jesus, this awareness of divine oneness was so transformative that it transcended his limited personal identity, the ego structure previously identified as a finite form. As his personal identity began to dissolve, Jesus did not cling. Instead, he embodied this realization of the Kingdom of God, teaching others through necessarily figurative and symbolic language.

This is not the proclamation of a human ego asserting personal divinity. This is the voice of limitless, formless being, speaking through a limited form. ⬚

_____

In part 2 we will explore how the non canonical gospels might further illustrate nondual themes.

Jesus' Non-Canonical Teachings of Nondual Reality (Part 2)

Previously, we explored how the canonical teachings of Jesus suggest a nondual reality. Now, we turn to the non-canonical Gospels, texts outside the biblical mainstream, which, in many instances, offer a more direct and explicit articulation of nondual themes.

Among the most significant of these texts is the Gospel of Thomas, considered by some as one of the earliest accounts of the teachings of Jesus. Thomas presents Jesus primarily as a wisdom teacher whose words point towards an inner realization. The canonical Gospels contain sayings about the Kingdom of God, which are often understood as a future external realm. In Thomas, the Kingdom is consistently portrayed as a present, internal reality. Saying 3 famously states, “If those who lead you say to you, ‘See, the kingdom is in the sky,’ then the birds of the sky will precede you. If they say to you, ‘It is in the sea,’ then the fish will precede you. Rather, the kingdom is inside of you, and it is outside of you.” This is a direct nondual assertion, dissolving the boundary between inner and outer. The divine reality, the Kingdom, is not a distant place to be reached after death or in a future era. It is an ever-present reality that encompasses both our inner being and the external experiences of the world. As such it is indivisible.

What is it, then, that is indivisible, ever-present, and knows our innermost thoughts? Is it the very thing in, of and by which everything and anything can ever be known?

Jesus says in Thomas 77: “I am the light that is over all things. It is I who am the All. From me did the All come forth, and unto me did the All extend. Split a piece of wood, and I am there. Lift up the stone, and you will find me there.” This is a radical “I Am” statement that transcends the personal. It is not the voice of a human ego claiming identification with a separate, transcendent God. It is the voice of realized Oneness, the nondual reality speaking through a human form. It declares the ultimate reality, the pure immanence of awareness, even in the most mundane activities of the physical world. Awareness creates no fundamental distinction between rich and poor, happy and sad, subject and object. The sense of differentiation is created by the mind, and the sense of separation is created by the belief in separation.

The non-canonical Gospels also echo and elaborate on the canonical hints regarding the necessity of transcending the obstacle posed by the perception of a separate self. Thomas, Saying 22 says: “When you make the two one, and when you make the inside like the outside and the outside like the inside, and the upper like the lower, and when you make the male and the female one and the same... then will you enter the kingdom [of the Father].” This is a clear call to investigate the dualistic perception that prevents the realization of oneness. Making the two one involves reconciling the perceived opposites that structure our experience—inner and outer, spirit and matter, male and female. It is the activity of honoring the necessary distinctions while seeing the underlying unity from which these distinctions arise.

The Gospel of Mary Magdalene further supports this emphasis on inner knowledge and the dissolution of illusory forms. In this text, the risen Savior teaches the disciples about the nature of matter, passion, and ignorance that obscures the spirit. Later chapters describe the soul's journey upwards, shedding layers of “powers” or forms of identification that hold it back.

These non-canonical texts often amplify the message found in the canonical Gospels. They consistently point inward, affirming that the divine reality, the Kingdom, the Truth, is not a distant entity or place, but an inherent, ever-present oneness. They provide explicit instructions on the path of understanding the dualities and structures of the separate self.

And they present the figure of the risen Christ speaking from a perspective of realized identity with the One, the “I Am,” the indivisible source and substance of existence. ⬚